Introduction

Three months ago, I started my first job in cybersecurity as an Application Security Engineer. My work focuses mostly on penetration testing our software products, exactly what I aspired to do while honing my skills on platforms like TryHackMe and Hack The Box.

Much of my preparation involved Capture the Flag (CTF) challenges, which simulate real-world hacking by uncovering hidden “flags” through exploiting vulnerabilities.

However, it’s important to recognize that CTFs are ultimately simulated exercises that don’t fully capture the complexities of real-world hacking. I was aware of this even during my training, so I approached my new role ready to experience firsthand how the reality of AppSec differs from the simulations.

In this post, I’d like to share a few key lessons I’ve learned in my short time in AppSec so far about how real-world work differs from CTF challenges.

Real Apps Are Complex

Often times, CTFs will have you hunting for vulnerabilities on applications made specifically for the challange. One thing these custom-built appliactions have in common is that they are usually tiny in scope.

They often are simple web applications with just enough functionality to support the intended challenge. There’s no unnecessary noise or rabbit holes, just what needs to be exploited to progress.

This makes total sense. An application made for a CTF filled with features that can’t be exploited would just waste both the player’s and the creator’s time. As a result, the source code for these challenge apps tend to be made up of only a handful of files that are easy to navigate and understand.

In contrast, real enterprise applications are massive. A large commercial app can have thousands of features, big and small. Even a single feature might have many tiny moving parts that need to be tested for vulnerabilities. This is a far cry from the humble attack surface from CTFs.

They are also complex in terms of code. The codebase for a single software product might span multiple projects and millions lines of code. The architecture can be so intricate that no single product feature exists in one place. Instead, it is dispersed across thousands of files, classes, and methods.

It should not come as a surprise that real-world applications are more complex, but you might think pentesting a complex application is just like testing a simple one, only on a larger scale. In reality, complexity compounds upon itself. An application that’s twice as complex isn’t just twice as hard to understand and exploit, it’s even harder.

Practicing application exploitation in simulated environments can teach you valuable techniques and skills, but it won’t fully prepare you for the sheer complexity of researching and exploiting real-world applications.

White-Box Everything

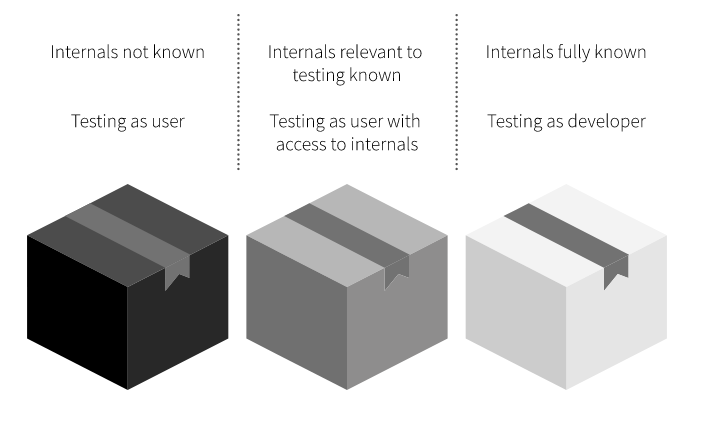

The different pentest "boxes".

If you practice on platfroms like Hack The Box, you’ll mostly be dealing with black-box pentesting. For most boxes, you start with just an IP address and maybe its operating system, so you’re almost entirely in the dark about how things work under the hood.

Occasionally, you might get access to an application’s source code through a Git repository or a remote file share, or maybe by exploiting local file reads on a web app. If it’s an executable, reverse engineering might give you a bit more insight. But even then, that’s not very common occurrence.

Training under these circumstances has its benefits. For example, it got me used to working with minimal context during pentests. I’ve learned to build a mental model of the target based on what I can observe or infer, rather than relying on privileged insights.

However, this approach doesn’t translate well into AppSec, where (in my experience) penetration tests are always done from a white-box perspective. This means you have access to source code, internal documentation, and even the developers themselves.

These resources provide an great level of insight into the application, allowing you to uncover vulnerabilities that would be very difficult (or even impossible) to find without them. However, I found that this level of insight can feel overwhelming, especially when you’re used to working with minimal context.

You might assume that having more information would simply make pentesting easier, but in my experience, it fundamentally changes the process. If you’re not familiar with white-box testing, it can feel disorienting. Add to this the complexity of real-world application codebases, and it becomes easy to get lost if you don’t have a solid methodology for integrating all these resources into your testing.

White-box testing isn’t just black-box with more information. It requires a different skill set. You need to know how to filter through all the details effectively, or you end up drowning in too much information. It’s a skill that requires active practice.

Lots of Research

Deep research may reveal all sorts of nasty bugs.

One of the most valuable skills you develop through CTF practice is learning to follow a structured methodology when performing penetration tests on a target.

There are many established methodologies to choose from, but they all start with an information-gathering phase. This step is about understanding the target’s details and inner workings before trying to exploit it.

CTFs do a great job of teaching you to research your target before exploiting it. However, in my experience, CTFs tend to place more emphasis on the exploitation phase, while in the real world, the balance is often skewed much more toward research and analysis.

To be fair, this could be because I’ve mostly worked on easy and medium-level Hack The Box machines, and things might be different with harder ones. That said, if I spend an hour on a box, roughly half of that time is spent on reconnaissance and research, with the rest spent figuring out and executing an exploit.

On the job, it’s a different story. I can easily spend days digging into an application’s features while assessing it from a security perspective. This involves reading code, analyzing logs, and running tests long before I can think about whether something is exploitable.

So, I don’t believe it’s realistic to expect to pop reverse shells as often on the job as you might in CTFs. In my experience, real-world penetration testing requires a lot of observation, research, and tinkering first and foremost.

No Assured Wins

To me, the most important mindset shift between hacking in CTFs and in the real world is accepting that you are not guaranteed to “win.”

In a CTF, you always know that the challenge was deliberately designed with an exploitable vulnerability and an intended solution. Even if you struggle, there’s the reassurance that, with persistence, you’ll eventually find something because the box was created for that purpose.

In the real world, that certainty is not there. When you’re testing actual software, the goal of its design and implementation was to eliminate vulnerabilities, not to create them for you to exploit. Unlike a CTF, there’s no promise of a “fair” exploit chain waiting to be discovered.

This means you don’t have the same guarantee of success. Sometimes, after thoroughly researching a target, you may find no vulnerabilities at all. And while that’s completely normal (it’s even a sign of secure development) it can still feel discouraging. Not finding anything after hours or days of effort can be a hit to your morale.

The way I cope with this is by convincing myself that there is always, without a doubt, a vulnerability to be found if I just keep trying hard enough. Even though this might not always be true, allowing myself to believe it keeps my creativity and enthusiasm alive. If you start entertaining the idea that your target is flawless and there’s nothing to find, it’s easy for your motivation and focus to drop. So, I find it best to keep my hopes up and act as though there’s always a way to win.

Conclusion

I highly recommend CTF practice for anyone without professional experience who wants to develop the skills and knowledge necessary to land their first job in offensive cybersecurity.

That said, there are many things that only real-world experience can teach you. In my experience, real pentesting is both more challenging and more rewarding than the simulations, so you have a lot to look forward to.

If you’re primarily learning about hacking through CTF platforms and want to prepare for a role in AppSec, here are three pieces of advice to complement your CTF practice:

-

If you’re not already comfortable reading and writing code, this is a skill you should absolutely prioritize. Analyzing source code is a significant part of white-box pentesting, so familiarize yourself with as many popular languages as you can. Certain tasks may also require you to write custom tools or scripts.

-

One thing I wish I had done more while preparing was to analyze open-source projects. This is excellent practice for white-box testing skills, and if you discover a vulnerability, you might even earn a CVE, which is a fantastic addition to your resume.

-

Research often involves documenting your findings so that other members of the AppSec team or developers can use them as a reference. Practice writing your research in a clear, structured, and professional manner to ensure it’s useful to others.

Although my experience is still limited, I hope this gives you some insight into what to expect when transitioning from CTF practice to real-world AppSec work.